Haitian Art

SPIRITS OF HAITI: SEQUINED VODOU FLAGS AND THEIR AFRICAN ORIGINS

In the last sixty years Haitian art has found its deserved place in the world history of art. The most spectacular Haitian art form is undoubtedly the glittering tradition of the sequin-covered Vodou flag or drapo Vodou. Vodou banners are important within the practice of the Haitian religion primarily because they are powerful liturgical objects. Originating directly from the practice of Vodou, drapo Vodou constitute an elaborate display of devotion and a dynamic invitation to any of the lwa (spirits of the Vodou pantheon). Used as a demarcation between sacred and secular, the flags are unfurled at the beginning of a ceremony, inviting the spirits to participate in the ritual. Drapo are amongst the most sacred and expensive ritual objects in the temple and the prices of some flags are so astronomical that some temples have gone bankrupt in order to pay for them. The typical ceremonial flag requires somewhere between 20,000 to 30,000 sequins. Depending on how many sewers are working on a piece, the finished product can take from a week to a full month.

Although sequined flags are an art form unique to Haiti, its origin evokes many possibilities including military and religious sources, inviting us to look at the countries of provenance of the Haitian slaves in the African continent.

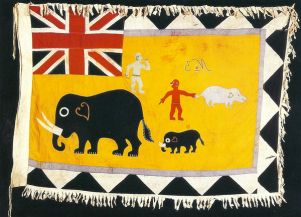

In Africa, flags and banners have long been used to express notions of cultural identity, military prowess, and religious affiliation. Ceremonial flags are indispensable ritual objects in many African and Afro-American societies and, as a whole, represent one of the most significant artistic continuities within the Afro-Atlantic world. Most, if not all, African and Afro-American ceremonial flags exemplify the dynamic mingling of African and European military, political, and religious traditions, which is a common trait of Afro-Atlantic culture. By the 1600s a wide range of flags were in use throughout the Western Africa coastal regions and figured prominently in the military and courtly rituals of major African states. Ceremonial flag traditions flourished during the colonial occupation of Africa and many have continued into the postcolonial era. The royal banners of the Fon kings of Dahomey (Benin) and the Fante Asafo military flags of Ghana encapsulate the African nationality and social performance in much the same way as Haitian drapo Vodou.

The Fante people live in fishing villages along the coast of Ghana and in past centuries the region was a centre for slave trading. The earliest Fante flags may have been painted or drawn on raffia cloth but, as is the case today, most flags were made of appliquéd trade cloth, which the Fante had in abundance. Flags, called frankaa, are a key item of Fante regalia. At annual festivals, flags are hung around the shrine and paraded through the village and can easily be handled by a flag-dancer during a festival or a ceremony with a spectacular dance-performance. While flags made before Ghanaian independence in 1957 have a version of the British Union Jack flag in the corner, the ones made afterwards display the national flag instead. Since the 1990s flags by the Fante people have become highly collectable outside Ghana.

Fon is a major West African ethnic and linguistic group in the country of Benin (Dahomey) and southwest Nigeria comprising more than 3,500,000 people. The Fon monarch used to appeared beneath colorfully appliquéd cloth-covered pavilions, umbrellas and banners bearing emblems of royal virtues and prerogatives. As in other sub-Saharan kingdoms, art was instrumental in emphasising the ruler's power. Their function was so important that the use of these objects was an exclusive prerogative of the royal family on penalty of death. According to Fon oral history, King Agonglo, who ruled just before the beginning of the slave trade from 1789 to 1797, commissioned the first royal banner. When an individual was elevated to royal status, he received a plain white cloth that he was expected to embellish over time promoting his achievements. With the abolishment of the monarchy by the French, members of the general population began using these fabrics in their homes as wall decorations or even pillowcases. By the mid-20th century, production of appliquéd textiles had become almost exclusively commercial.

During the slave period circumstances appear to have made transplanting these arts to Haiti almost impossible. Amongst the Africans who arrived in Haiti with no possessions, after six weeks of near starvation without sun, and crowded in the holds of slave ships, some could have indeed been artists, but under these conditions the opportunity for artistic expression was lacking. However, the similarities of style and function seem to indicate that the knowledge of skilful and imaginative arts embodied in the Africans, when they came to Haiti, seem to have survived in the tradition of drapo Vodou.

Gabriel Toso

Comments

BTW talking of Haitians and Fon people; for those of you interested in knowing more about your African roots, visit my black history website at mawuvi.com/African-Black-History/About-Us-Revealing-African-Ancestral-Secrets

Add comment

Web favorites

- Non Gamstop Casinos

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casinos

- Betting Sites

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casino UK

- Non Gamstop Casinos UK

- Sports Betting Sites Not On Gamstop

- UK Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Gambling Sites Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casinos

- Non Gamstop Casinos

- UK Online Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casinos UK

- Non Gamstop Casino Sites UK

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Slots Not On Gamstop

- Casino Not On Gamstop

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casino Not On Gamstop

- Slots Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casino

Latest comments

- “MEET THE ADEBANJOS”

Oh my God this is sooo funny. It’s a shame we can'... More...

15.02.12 20:12 - National African American Cong...

The Language You Cry In (1999) 1999. 53 minutes. S... More...

13.01.12 20:16 - Haitian Art

What is the union-jack doing in the first image of... More...

12.01.12 23:27

Gone too soon

Maya Angelou,(April 4, 1928 - May 28, 2014) was an American author and poet. She published seven autobiographies, three books of essays, and several books of poetry, and was credited with a list of plays, movies, and television shows spanning more than 50 years.

- adoption ad

- books

- info

Adoption explained

Adoption is a way of giving a child a new permanent family because they cannot be brought up by their own parents. If you adopt a child you become the...

READMORE