Obituary

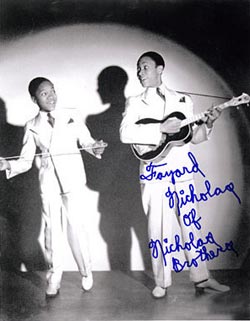

Fayard

Antonio Nicholas

(1914 - 24th January 2006)

Dancer Supreme

The death of Fayard Nicholas the elder of the world

famous Nicholas brothers, brings to an end the story

of one of the greatest dance duos the twentieth century

had ever seen. The death of Fayard Nicholas the elder of the world

famous Nicholas brothers, brings to an end the story

of one of the greatest dance duos the twentieth century

had ever seen.

Harold (1921-2000) and Fayard Nicholas,

child prodigies from Philadelphia, built on the tradition

of brilliant African American dancers such as Bill ‘Bojangles’ Robinson,

and are the ancestors of subsequent generations of

black entertainers viewed as exceptional dancers

such as James Brown, Michael Jackson, Usher.

Bursting onto the black vaudeville scene in the 1930s,

as infants, they were so talented that despite the

heavy racial restrictions of the day, they ended

up on Broadway in musical revues and Hollywood in

musical films in record time, whilst still quite

young. Those same racial restrictions though, meant

that despite being vastly superior in range, interpretive

gifts, and technique to Fred Astaire, and having

greater flexibility and poise than Gene Kelly, in

films they were confined to a very limited arena

compared to the two white male ‘superstar’ dancers.

Fayard and Harold were literally born into show

business. Their father Ulysses ran a band at the

Standard Theatre in Philadelphia in which their mother

Viola played piano. Fayard was attending the theatre

and seeing the musicians, actors and dancers rehearsing

and performing from when he was toddler. Fayard started

out by imitating for his brother at home and other

children in their neighbourhood what he was seeing

on stage- the dancing particularly tap, the acrobatics,

the comic timing - Harold seven years younger but

very talented, started out by mimicking Fayard. They

were so good that when Fayard was 14 they made their

stage debut. They rapidly became a local sensation

appearing in theatres in Philadelphia where the manager

of the famous Lafayette theatre in New York saw them.

Their parents were encouraging, -Fayard to pursue

dance and maintained his father’s advice to

be expressive and use their arms when they danced.

By 1932, they were appearing at the internationally

famous Cotton Club in Harlem - Fayard was 17,

Harold 10 - with great artists like Cab Calloway

and Duke Ellington. What made the Nicholas brothers

so

unique was that whilst the dancing they did was rooted

in tap, they incorporated a  elements of other styles

resulting in a dazzling display of spins, twists,

leaps, and acrobatics -each brother mirroring

the other- that had never been seen before. Despite

its segregated approach Hollywood grabbed them in

the early 1930s and that decade saw them moving between

film (Pie Pie Blackbird, 1932, Kid Millions 1934,

The Big Broadcast 1936) and Broadway (in the legendary

Ziegfield Follies, and in the Blackbirds

of 1936).

In the Broadway production their sensational act

would stop the show every night, and they were eagerly

welcomed and feted in Europe, where they saw great

European ballet companies and ever innovative, incorporated

some classical ballet movements into their dance.

This approach is the reason why calling the Nicholas

brothers ‘the world’s greatest tap dancers’ is

actually to sell them short. Like many a genius child

prodigy before them, they created something unique,

a blend of various dance disciplines, tap, modern,

jazz ballet and classical ballet being the most obvious.

Georges Balanchine the great ballet choreographer

recognised immense talent when he saw it and invited

them to appear in a musical he was doing the choreography

for on Broadway. elements of other styles

resulting in a dazzling display of spins, twists,

leaps, and acrobatics -each brother mirroring

the other- that had never been seen before. Despite

its segregated approach Hollywood grabbed them in

the early 1930s and that decade saw them moving between

film (Pie Pie Blackbird, 1932, Kid Millions 1934,

The Big Broadcast 1936) and Broadway (in the legendary

Ziegfield Follies, and in the Blackbirds

of 1936).

In the Broadway production their sensational act

would stop the show every night, and they were eagerly

welcomed and feted in Europe, where they saw great

European ballet companies and ever innovative, incorporated

some classical ballet movements into their dance.

This approach is the reason why calling the Nicholas

brothers ‘the world’s greatest tap dancers’ is

actually to sell them short. Like many a genius child

prodigy before them, they created something unique,

a blend of various dance disciplines, tap, modern,

jazz ballet and classical ballet being the most obvious.

Georges Balanchine the great ballet choreographer

recognised immense talent when he saw it and invited

them to appear in a musical he was doing the choreography

for on Broadway.

In the 1940s they appeared in 6 musicals for the

studio 20th Century Fox. Their part of the films

was always something that could stand alone, not

integral to the plot or action, so that it could

be cut out of the film in order not to offend white

audiences in the southern US states. The sensational

impact they made in the films meant they were in

international demand. The Nicholas brother went on

to do tours in various parts of the world, including

South America and Europe. They appeared in front

of the King of England in 1948 at the London Palladium.

Despite this acclaim, the apartheid-like system in

their country meant that whilst working at the film

studio they could be refused admission to the in

house restaurant. It has been reported that famed

director David Selznick had to intervene and shame

the relevant restaurant head by reminding him that

it was due the brothers’ appearance in their

films, that there was a studio. Little wonder that

staying in Europe in the 1950s became more and more

attractive, and as many African Americans before

them, they found France particularly welcoming. In

1958 Fayard returned to the US leaving Harold behind

and they worked apart for seven  years. Changes in

the entertainment industry - the end of vaudeville,

a different approach to musical theatre - meant that

their form of dance was becoming less popular, but

black film stars were not yet commonplace either.

Harold was for a time married to the only black female

film star of her day - Dorothy Dandridge - but any

contacts through that and their own long involvement

in Hollywood

could not translate into chances for decent lead

or character roles. In the 1960s the brothers were

together again on US television. But the glory days

were gone and work did not reach its former heights.

In the 1970s, interest in tap dancing started to

revive. As often happens, regardless of fashion in

their own country, they had not been forgotten on

the other side of the Atlantic. First the BBC in

1985 in a programme called Cotton Club Comes

to the Ritz featured them, then Channel 4 did a documentary

in 1989 We Sing and We Dance: The Nicholas Brothers and

the same year Fayard won a Tony award for choreographing

a Broadway hit Black and Blue. years. Changes in

the entertainment industry - the end of vaudeville,

a different approach to musical theatre - meant that

their form of dance was becoming less popular, but

black film stars were not yet commonplace either.

Harold was for a time married to the only black female

film star of her day - Dorothy Dandridge - but any

contacts through that and their own long involvement

in Hollywood

could not translate into chances for decent lead

or character roles. In the 1960s the brothers were

together again on US television. But the glory days

were gone and work did not reach its former heights.

In the 1970s, interest in tap dancing started to

revive. As often happens, regardless of fashion in

their own country, they had not been forgotten on

the other side of the Atlantic. First the BBC in

1985 in a programme called Cotton Club Comes

to the Ritz featured them, then Channel 4 did a documentary

in 1989 We Sing and We Dance: The Nicholas Brothers and

the same year Fayard won a Tony award for choreographing

a Broadway hit Black and Blue.

They had lived and worked long enough to be rediscovered

and become national institutions-although they didn’t

receive the kind of financial package that gave them

the sources of income actors now have from repeat

TV showing of their films. Famous pupils such as

Debbie Allen and Janet and Michael Jackson, famous

master dancers such as Gregory Hines and Barishnikov

lauded them and a whole new generation discovered

them. Age though took its toll and arthritis in the

1980s/90s meant an end to Fayard’s flexibility

as a dancer. By the time Harold Nicholas died in

2000, they had appeared before nine US presidents,

a star on the Hollywood walk of fame, and an honorary

doctorate from Harvard. A special concert was staged

in their honour at Carnegie Hall in 1998.

The Nicholas Brothers’ legacy lives on in the

fantastic, gravity defying movements of those who

have mastered various forms of African-American modern

dance including breakdancing.

Marsha Prescod

|