BLACK

DANCE IN ENGLAND: THE PATHWAY HERE

by Hilary Carty

Hilary Carty was formerly Director of Dance

at the Arts Council of England. From the perspectives

of

both artist/choreographer in the 80s and policy-maker

from the mid 90s, she experienced at first hand the

highs and lows of black dance in England. We asked

her to capture those insights for future generations…

Looking across Europe, Britain is fortunate

in having one of the most diverse portfolios of

artists consistently funded. The diversity of dance

forms

spans from the traditional to the contemporary

with every nuance at the margins of both. Even

with the

decline in the number of companies witnessed in

the last couple of decades, the range is notable.

That

diversity is undoubtedly to be celebrated - it

also presents us with a challenge - that

of definition.

Today’s artists defy strict

categorisations and, as we look at the many hybrid

upon hybrid forms

created in the diverse cultural environment that

Britain has become, it is worth starting this discussion

by exploring the rather unwieldy and unspecific

term ‘black

dance’ itself.

Black Dance or African Dance?

‘Black’ is essentially a political term

used in the United States during the civil rights

movement to positively affirm the history and culture

of African

Americans. In the British context, however, the

phrase ‘black’ whilst

being used to identify African descendents, was

extended to identify and affirm a positive affiliation

with

people who have a history of colonisation and oppression

by the British - hence it being used to include

Asian communities and even the Irish in some instances.

With such a loose coalition of meanings, it becomes

difficult to comfortably use the word ‘black’ in

artistic terms - it is subjective and very much

open to interpretation.

Within the arts sector,

there has been serious debate on titles for over

30 years - many conferences

and articles have tried to dissect every nuance without

comprehensive success. I will not spend a lot

of time on that here, but suffice to say that language

is a living entity which develops as communities

develop - there is little ‘right or wrong’ in

a living language; terms that appear apt within

one decade become tainted and discarded in

the next. Within the arts sector,

there has been serious debate on titles for over

30 years - many conferences

and articles have tried to dissect every nuance without

comprehensive success. I will not spend a lot

of time on that here, but suffice to say that language

is a living entity which develops as communities

develop - there is little ‘right or wrong’ in

a living language; terms that appear apt within

one decade become tainted and discarded in

the next.

This discussion of black dance will focus around

dance that has its root in the African cultural

idioms whether it be dance that is traditional,

classical,

contemporary, modern, modernist, new or hybrid

developments from that base culture. In the

UK, when we use the

term ‘African’ dance, there is often

a connotation that we are talking about traditional

dance - such as that performed by Adzido

for instance. But it is important to remember

that, just

as we can talk about classical ballet, neo-classical

ballet and contemporary ballet, then we can

equally use that range of terms for other

types of dance

such as African or South Asian dance forms.

No living culture is static.

It is equally important

in this artistic context to ensure that

we are talking about more than

a geographical entity… for any

dance form to have longevity it must

be capable of being

codified through

a language or vocabulary of movement

that conforms to a known

aesthetic - and it is in this sense that

I use the term African dance. Whilst

there is, as yet,

little

codified technique, there is a clear

genre of movements that are common across

African dance

forms and lead

us to the basics of the African dance

technique: grounded earth bound movements,

a flexed or relaxed

foot, bent knees and bent elbows, curved

spine, rotating hips and a loose torso

ready to flex

both sideways

and back. These are some of the key characteristics

that define the African dance genre.

So whether we are looking at Adzido with

its classical/traditional

style or Caribbean dance where Africa

met Europe and the interplay of cultures

created both the

Dinkie

Minnie and the Jamaican Quadrille. Or

when we look at some of the British exponents

that trace

a line

directly from Africa (Badejo Arts) or

via the Caribbean (Irie! Dance Theatre),

there is still

enough aesthetic

vocabulary to trace it to the kernel

of African dance forms.

The Trail Blazers

Perhaps some of the most significant developments

in black dance came after the war, with the creation

of Les Ballet Negres in 1946.

This group of dancers created works which drew

upon an African/Caribbean

heritage and begun with a sellout 8 week season - a

feat within itself. Les Ballet Negres could not

get funding though and survived only on box-office

receipts.

Hence, despite tremendous popularity here and

across Europe - it folded in 1952.

The 50s saw the building of the British Ballet

repertoire. By the end of the 60s contemporary

dance had gained

a firm foothold in England but it was not until

the 70s that things began to move again in terms

of black

dance here. The Early 70s saw the arrival of

some of the pioneers of African dance in the

UK via the

group Sankofa from Ghana.

Following a very successful British tour, many

of the artists stayed here

and became cultural ambassadors, travelling

the length

and breadth of the Country and teaching the

Ghanaian dance repertory. Soon there were dance

troupes

sprouting up all over the Country - mainly

doing Ghanaian dance forms.

It is hard now to imagine the explosion of groups

that were around in the 1980s - it was a truly

exciting time - over 20 groups of great popularity:

Ekome,

Kokuma, Irie! Lanzel, Kizzie, Dagarti, Delado,

Dance de l’Afrique, Phoenix, Dance Co 7, Badejo Arts… The

range of work spanned the traditional to the experimental - from

the fundamentals to several different fusions

of the contemporary.

Ekome was perhaps the most successful,

touring to sell-out concerts in venues such as the

Leicester

Haymarket and Derby Playhouse. Based

in Bristol, Ekome’s repertoire consisted mainly

of traditional Ghanaian dances taught by artists

such as George

Dzikunu (founder and former Artistic

Director of Adzido). As a dancer trained in contemporary

and

ballet techniques I had never seen anything

like

Ekome and it fairly blew my mind! It

was amazing to see dancers Barry and Angie Anderson

on the

stage performing with such authority

and style. And the

fact that they were doing traditional

African dance was a really powerful signal - a positive

affirmation

of identity.

Other groups producing traditional African dance

included Lanzel (Wolverhampton), Dance

de l‘Afrique (Birmingham), Dagarti

Arts (London) and Delado (Liverpool).

To appreciate the scale and impact of

this work it is worth noting that all

these groups had work - some

in mainstream theatres and arts centres whilst other

groups performed in smaller scale community venues

and festivals - but there was no

shortage of groups from which to choose.

Contemporary Legacies

But doing traditional African dance was not

enough - Germaine

Acogny - a key exponent of contemporary African

dance from Senegal summed it up as follows: ‘African

dance comes from the villages of Africa - but

there is now the Africa of cities, of skyscrapers.

I hope the dance of the villages will always

exist, but we cannot preserve dance purely as

a museum culture.

It must grow. If it does not develop it will

die, and we will have nothing. What will our

generation

leave to our grandchildren?’

In Leicester the Grassroots Dance Company started

in 1974, was one of the earliest groups embracing

a Caribbean aesthetic. It sought to give a voice

to young black dancers to express their own creativity.

MAAS Movers started in London in

1977 - by

a group of trained contemporary dancers

who were seeking to blend African/Caribbean dance

with

their contemporary dance training.

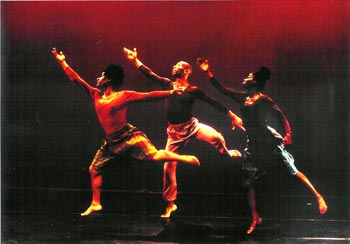

In London in 1978 Dance Company 7 (see

picture right) was formed when Carl Campbell

sought to use Caribbean dance as

a means of expressing his creativity and

reaching out

to young black children growing up in London’s

inner cities. In London in 1978 Dance Company 7 (see

picture right) was formed when Carl Campbell

sought to use Caribbean dance as

a means of expressing his creativity and

reaching out

to young black children growing up in London’s

inner cities.

In

Birmingham a group of artists were seeking

to use the traditional African dance vocabulary

as a base technique but to move on to include

something of the contemporary British black experience - having

reveled in the culture of Africa artists

began to question what their generation of young

people

could

contribute themselves? Kokuma emerged in Birmingham

in 1978.

By 1981, Phoenix was formed in

Leeds by three young men who used the social dances

from the streets

of Harehills - funk, reggae and

jazz to combine with a very athletic

contemporary dance, which

took the country by storm.

Corinne Bougaard established

Union Dance in 1983 with a deliberate aim to embrace

a broad multi-cultural

approach to dance, hence its title.

Adzido Pan

African Dance Ensemble began in 1984, embracing

a rounded production format. Whilst

Ekome stunned audiences with its renditions of traditional

works, Adzido sought to mold the traditional

dances around a theme or poetry, creating a more epic style

with a company of over 30 dancers and musicians.

Irie! Dance Theatre (see

pic left) began in 1986 - arising

out of the Caribbean Focus year-long celebration

of the arts of the Caribbean. From the outset

Artistic Director Beverley Glean sought to work

with young

artists and use a fusion of the dances from the

Caribbean with elements of popular black culture

to have relevance

to London’s black youth.

So works like Caribbean Suite

and Reggae ina yu Jegge placed

Merenge and

Quadrille alongside popular reggae tunes. Irie! Dance Theatre (see

pic left) began in 1986 - arising

out of the Caribbean Focus year-long celebration

of the arts of the Caribbean. From the outset

Artistic Director Beverley Glean sought to work

with young

artists and use a fusion of the dances from the

Caribbean with elements of popular black culture

to have relevance

to London’s black youth.

So works like Caribbean Suite

and Reggae ina yu Jegge placed

Merenge and

Quadrille alongside popular reggae tunes.

The Midlands was incredibly strong in terms

of black dance, with a critical

mass of groups and

key individuals

living there - not surprising

therefore that it was in the

Midlands that the Black

Dance Development

Trust was formed,

under the Directorship of Bob

Ramdhanie, a key activist in

the field. One of the highlights

of the calendar from the mid

to late 80s was

its Black Dance Summer School - the first

taking place in Leicester in 1985. The Summer

Schools were

amazing - tutors from

Ghana, Senegal, Nigeria and

Jamaica working in intensive

classes teaching

technique, choreography, history

and social context. The debates

were heated and went on well

into

the night as we were taught

how to trace the origins

of contemporary movement styles

and Caribbean dance styles

to their African roots.

As we moved into the 1990’s yet more contemporary-facing

groups emerged, such as RJC in

1991 and Sheron Wray’s JazzXchange in 1992. Bunty

Matthias had huge

impact in London in the mid 1990s selling out

the Queen

Elizabeth Hall and more latterly, projects such

as Nubian Steps and the Hip

Festival have given

a voice

to young black choreographers. Artists such as

Jonzi D and Kompany

Malakhi are currently using

hip-hop

and other street dances to ignite audiences across

the Country, whilst the London Dance

House is

seeking to establish a base for artists and companies.

Current Questions - Future Moves

If we look at the current state of ‘black

dance’ we

see a very mixed picture. There are artists developing

new works, which are creative, exciting and accessible,

but the overall picture is not one of great health. ‘Time

for Change’ by Hermin McIntosh (commissioned

by the Arts Council in 1999) highlighted a key

issue being the lack of infrastructure - the

infrastructure for black dance remains weak,

and the picture is

much the same across the spectrum of black arts.

To

begin to understand how we could have got here

from such great times in the 1980s, one

might

perhaps look back at how black arts have been

supported. In the 70s and early 80s, much of the

funding

came

through social rather than artistic sources - when

Adzido began in 1984, it was under the auspices

of the Manpower Services Commission. Kokuma was

supported

by the probation service, and the majority of

groups received small pockets of funding from

Local Authority

Social Services and Education budgets rather

than artistic ones. Hence, it was not felt essential

to

apply high artistic judgments to the work, and

groups were not required to stretch their creativity

or

artistic competitiveness in this ‘community/outreach’ context. Picture Right is Dejo Arts To

begin to understand how we could have got here

from such great times in the 1980s, one

might

perhaps look back at how black arts have been

supported. In the 70s and early 80s, much of the

funding

came

through social rather than artistic sources - when

Adzido began in 1984, it was under the auspices

of the Manpower Services Commission. Kokuma was

supported

by the probation service, and the majority of

groups received small pockets of funding from

Local Authority

Social Services and Education budgets rather

than artistic ones. Hence, it was not felt essential

to

apply high artistic judgments to the work, and

groups were not required to stretch their creativity

or

artistic competitiveness in this ‘community/outreach’ context. Picture Right is Dejo Arts

It took time for the arts community to embrace

the arts of other cultures from an aesthetic

rather

than social/community development perspective and this

more inclusive approach clashed rather dynamically

with a decline in resources.

The early 1990s

brought about a time of recession - cuts in funding

for the arts became commonplace

and hard decisions had to be made about where

and what to support. Quite naturally, the artistic

criteria became paramount and, also naturally considering

the recent history, a number of groups were found

lacking. Peter Badejo OBE summed it up in his

paper What is Black Dance in 1993:

"Within ten years half

the companies performing African peoples’ dance forms in existence

have collapsed - there

was no solid foundation for them to exist

on. When funding decisions were based on

non-aesthetic

criteria,

there were numerous companies but they

were denied artistic respect. When artistic

considerations

become the criteria - the base

funding was removed and the structure

collapsed."

The

Arts Council acknowledged the gap in

the infrastructure for black arts. In previous years

it pushed to

reach a target spend of 4% for black arts - a

figure quickly achieved and consistently surpassed

by its

Dance Department. More recently the Arts Capital

Programme provided no less than £29m to

support culturally diverse projects across the

Country. The

impact of this will be seen over the coming decade.

But key to the success of future development

is continuing the partnership developed after ‘Time

for Change’ with

artists and activists to address the

issues of development from multiple angles

- covering aesthetics,

creativity

and artform development; presentation

and touring; advocacy; strategic development;

infrastructural

development; and training and education.

It is important to use the energies of today’s

creative individuals to match and

stimulate the broad-based initiatives that will make

a difference

in the presentation,

funding and structural development

of black dance in the future.

Reprint Courtesy of

ADAD | September 2003

|